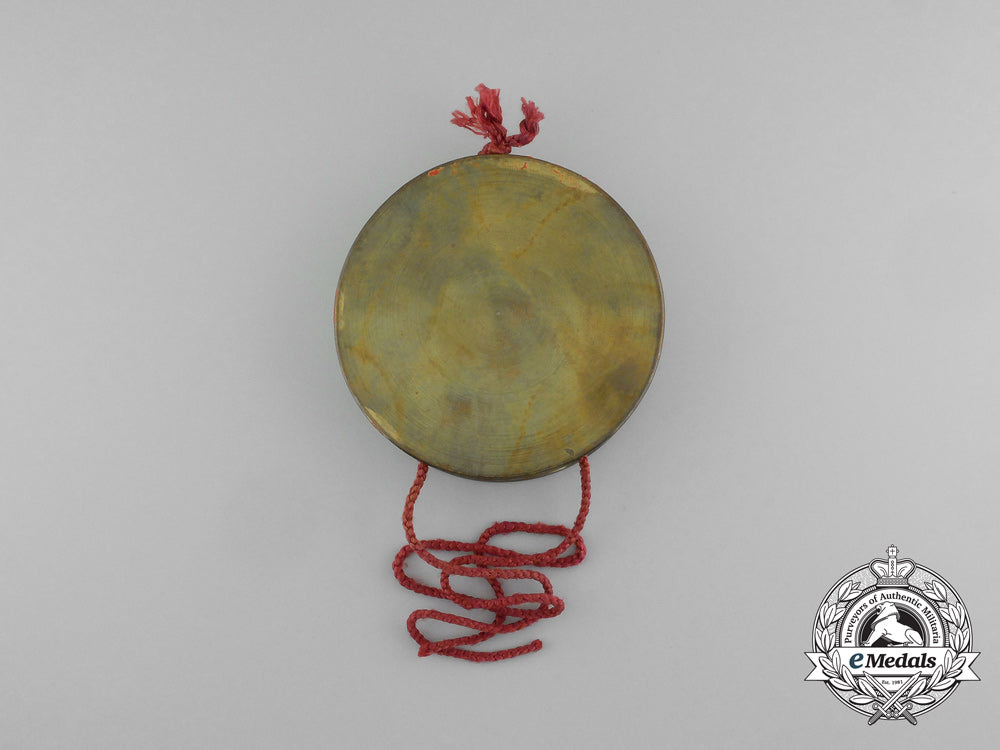

Italy (Parma): c. 1816-1847 Seal in red wax, likely having been accompanied by an award document for the Grandmaster of the Order of Constantine, illustrating the Royal coat-of-arms of Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma in the centre, surrounded by the Latin inscription "MARIA LUDOVICA PARM PLAC ETC DUX S ORD CONST MAGN MAGISTER", the seal encased in a two-piece shallow circular container in brass, three holes in the brass side wall of the bottom plate housing the wax seal, with two cords in red embroidery projecting through the two holes on one side, while the other ends of the cord pass through the wax, exiting via a hole on the opposite side and are tied in a knot, 80 mm in diameter, a 24 mm long piece missing in the raised rim of the wax seal framing "MARIA" near the base, the remainder of the wax seal remaining intact, the brass container without dents, near extremely fine.

Footnote: Marie Louise (Maria Ludovica Leopoldina Franziska Therese Josepha Lucia; Italian: Maria Luigia Leopoldina Francesca Teresa Giuseppa Lucia; December 12, 1791 - December 17, 1847) was an Austrian archduchess who reigned as Duchess of Parma from 1814 until her death. She was Napoleon's second wife and, as such, Empress of the French from 1810 to 1814. As the eldest child of the Habsburg Emperor Francis II of Austria and his second wife, Maria Theresa of Naples and Sicily, Marie Louise grew up during a period of continuous conflict between Austria and revolutionary France. A series of military defeats at the hands of Napoleon Bonaparte had inflicted a heavy human toll on Austria and led Francis to dissolve the Holy Roman Empire. The end of the War of the Fifth Coalition resulted in the marriage of Napoleon and Marie Louise in 1810, which ushered in a brief period of peace and friendship between Austria and the French Empire. Marie Louise dutifully agreed to the marriage despite being raised to despise France. She was an obedient wife and was adored by Napoleon, who had been eager to marry a member of one of Europe's leading royal houses to cement his relatively young Empire. With Napoleon, she bore a son, styled the King of Rome at birth, later Duke of Reichstadt, who briefly succeeded him as Napoleon II. Napoleon's fortunes changed dramatically in 1812 after his failed invasion of Russia. The European powers, including Austria, resumed hostilities towards France in the War of the Sixth Coalition, which ended with the abdication of Napoleon and his exile to Elba. The 1814 Treaty of Fontainebleau handed over the Duchies of Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla to Empress Marie Louise. She would come to rule the duchies until her death. In the summer of 1814, Emperor Francis sent Count Adam Albert von Neipperg to accompany Marie Louise to the spa town of Aix-les-Bains, to prevent her from joining Napoleon on Elba. Neipperg was a confidant of Count Metternich and an enemy of Napoleon. Marie Louise fell in love with Neipperg. He became her chamberlain and her advocate at the Congress of Vienna. News of the relationship was not received well by the French and the Austrian public. When Napoleon escaped in March 1815 and reinstated his rule, the Allies once again declared war. Marie Louise was asked by her stepmother to join in the processions to pray for the success of the Austrian armies but rejected the insulting invitation. She passed a message to Napoleon's private secretary, Claude François de Méneval, who was about to return to France: "I hope he will understand the misery of my position ... I shall never assent to a divorce, but I flatter myself that he will not oppose an amicable separation, and that he will not bear any ill feeling towards me ... This separation has become imperative; it will in no way affect the feelings of esteem and gratitude that I preserve." Napoleon was defeated for the last time at the Battle of Waterloo and was exiled to Saint Helena from October 1815. Napoleon made no further attempt to contact her personally. The Congress of Vienna recognized Marie Louise as ruler of Parma, Piacenza, and Guastalla, but prevented her from bringing her son to Italy. It also made her Duchess of Parma for her life only, as the Allies did not want a descendant of Napoleon to have a hereditary claim over Parma. Marie Louise departed for Parma on March 7, 1816, accompanied by Count Adam Albert von Neipperg. She entered the duchy on April 18th, later writing to her father: "People welcomed me with such enthusiasm that I had tears in my eyes." She largely left the running of day-to-day affairs to Neipperg, who received instructions from Metternich. In December 1816, Marie Louise removed the incumbent prime minister and installed Neipperg. She and Neipperg had three children: Albertine, Countess of Montenuovo (1817-1867), who married Luigi Sanvitale, Count of Fontanellato; William Albert, Count of Montenuovo, who later created Prince of Montenuovo (1819-1895) and married Countess Juliana Batthyány von Németújvár; and Mathilde, Countess of Montenuovo (1822-c.1823). Napoleon died on May 5, 1821. Three months later, on August 8th, Marie Louise married Neipperg morganatically (defined as a marriage between a member of a royal or noble family and a person of inferior rank, in which the rank of the inferior partner remains unchanged and the children of the marriage do not succeed to the titles, fiefs, or entailed property of the parent of higher rank), her second marriage. Neipperg died of heart problems on February 22, 1829, devastating Marie Louise. She was banned by Austria from mourning in public. Her first son, then known as "Franz," was given the title Duke of Reichstadt in 1818. Franz lived at the Austrian court, where he was shown great affection by his grandfather, but was constantly undermined by Austrian ministers and nationalists, who did their best to sideline him to become an irrelevance. Franz grew resentful at his Austrian relatives and his mother for their lack of support, and began identifying as Napoleon II. and surrounding himself with French courtiers. The relationship with his mother broke down to such an extent that he once remarked "If Josephine had been my mother, my father would not have been buried at Saint Helena, and I should not be at Vienna. My mother is kind but weak; she was not the wife my father deserved; Josephine was." However, before anything could become of Napoleon II, he died at the age of 21 in Vienna in 1832, after suffering from tuberculosis. The year 1831 saw the outbreak of the Carbonari-led uprisings in Italy. In Parma, protesters gathered in the streets to denounce the Austrian-appointed prime minister Josef von Werklein. Marie Louise did not know what to do and wanted to leave the city, but was prevented from doing so by the protesters, who saw her as someone who would listen to their demands. She managed to leave Parma between February 14th and 15th, and a provisional government, led by Count Filippo Luigi Linati, was formed. At Piacenza, she wrote to her father, asking him to replace Werklein. Francis sent in Austrian troops, which crushed the rebellion. To avoid further turmoil, Marie Louise granted amnesty to the dissidents on September 29th. Metternich sent Count Charles-René de Bombelles to Marie Louise's household in 1833, as her chamberlain. Six months after his arrival, on February 17, 1834, she married him, again morganatically. She would continue to reign for almost another fourteen years. Marie Louise fell ill on December 9, 1847 and her condition worsened over the next few days. On December 17th, she passed out after vomiting and never woke up again. She died that evening, five days after her 56th birthday, the cause of death determined to be pleurisy (inflammation of the pleurae, which impairs their lubricating function and causes pain when breathing, caused by pneumonia and other diseases of the chest or abdomen). Her body was transferred back to Vienna and buried at the Imperial Crypt.