LOADING ...

In response to evolving domestic opinion, eMedals Inc has made the conscious decision to remove the presentation of German Third Reich historical artifacts from our online catalogue. For three decades, eMedals Inc has made an effort to preserve history in all its forms. As historians and researchers, we have managed sensitive articles and materials with the greatest of care and respect for their past and present social context. We acknowledge the growing sentiments put forth by the Canadian public and have taken proactive actions to address this opinion.

Germany, Nsdap. A Collection Of Letters Sent Between Widow Of Seyß-Inquart & Swiss High Traitor Josef Barwirsch, 1965-1967

Germany, Nsdap. A Collection Of Letters Sent Between Widow Of Seyß-Inquart & Swiss High Traitor Josef Barwirsch, 1965-1967

SKU: ITEM: G45754

0% Buyer's Premium

Current Bid:

Your Max Bid:

Bid History:

Time Remaining:

Couldn't load pickup availability

Shipping Details

Shipping Details

eMedals offers rapid domestic and international shipping. Orders received prior to 12:00pm (EST) will be shipped on the same business day.* Orders placed on Canadian Federal holidays will be dispatched the subsequent business day. Courier tracking numbers are provided for all shipments. All items purchased from eMedals can be returned for a full monetary refund or merchandise credit, providing the criteria presented in our Terms & Conditions are met. *Please note that the addition of a COA may impact dispatch time.

Shipping Details

eMedals offers rapid domestic and international shipping. Orders received prior to 12:00pm (EST) will be shipped on the same business day.* Orders placed on Canadian Federal holidays will be dispatched the subsequent business day. Courier tracking numbers are provided for all shipments. All items purchased from eMedals can be returned for a full monetary refund or merchandise credit, providing the criteria presented in our Terms & Conditions are met. *Please note that the addition of a COA may impact dispatch time.

Description

Description

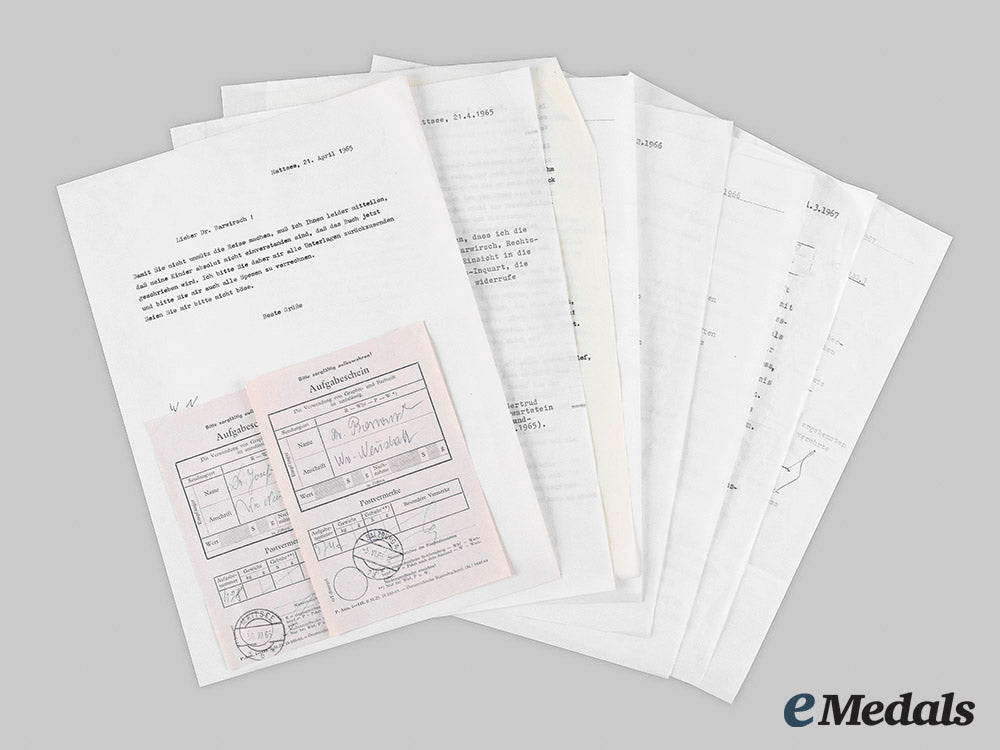

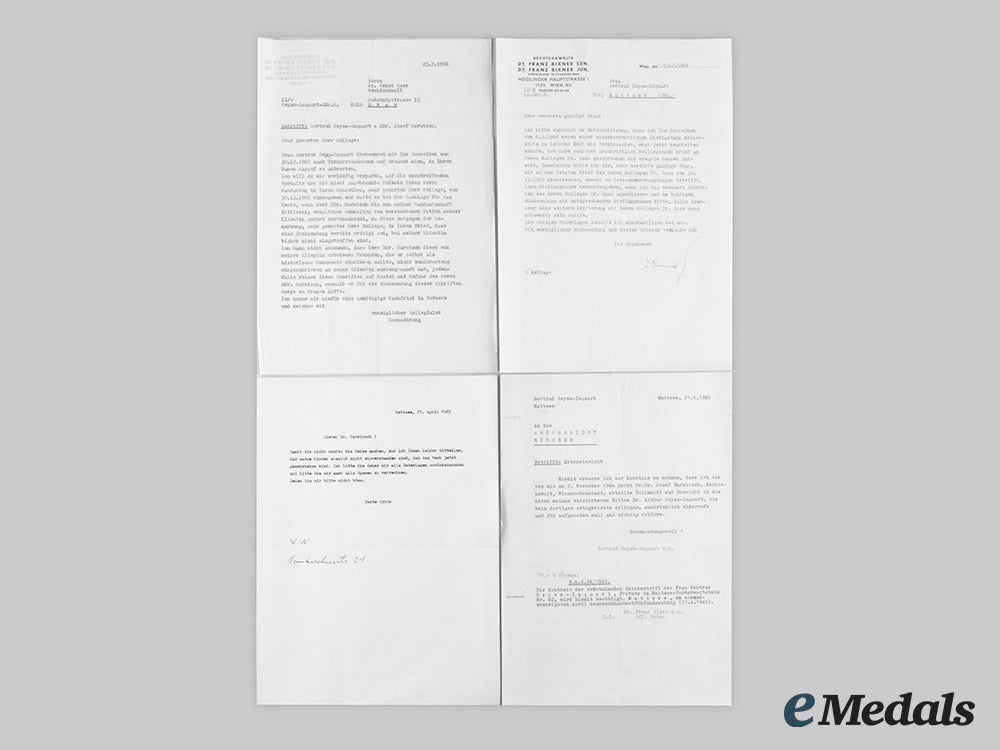

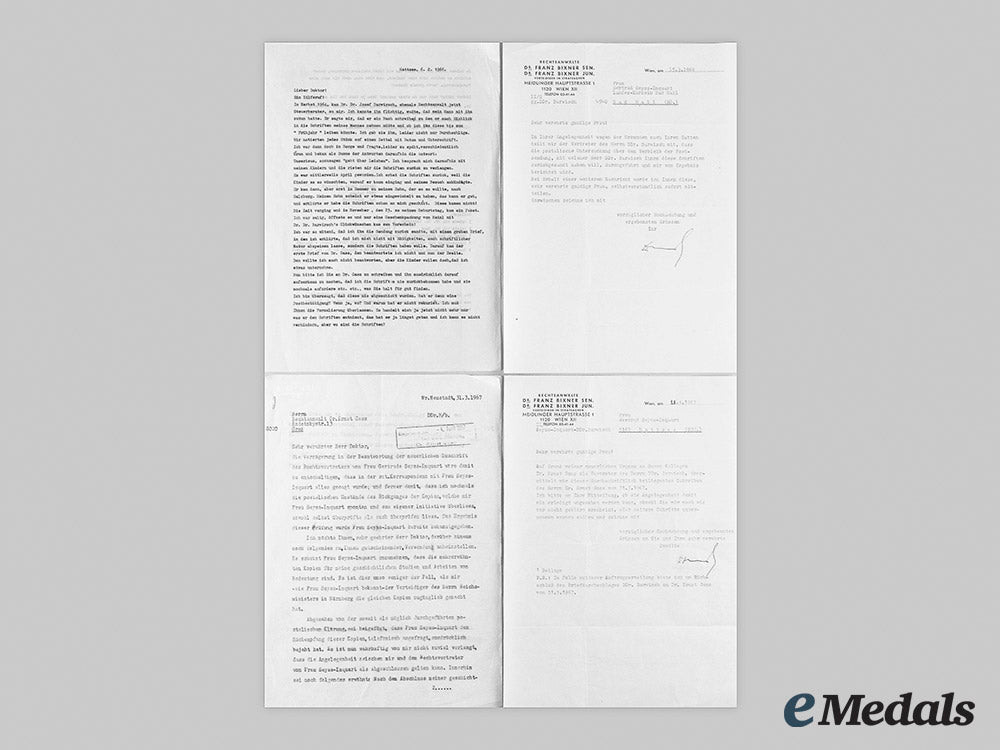

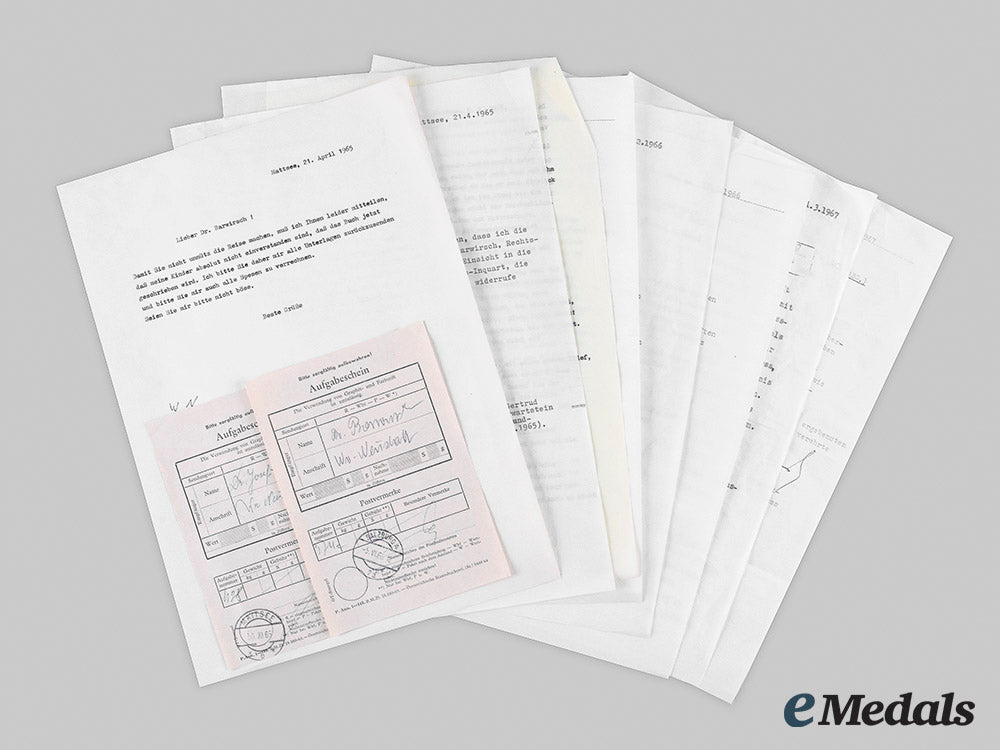

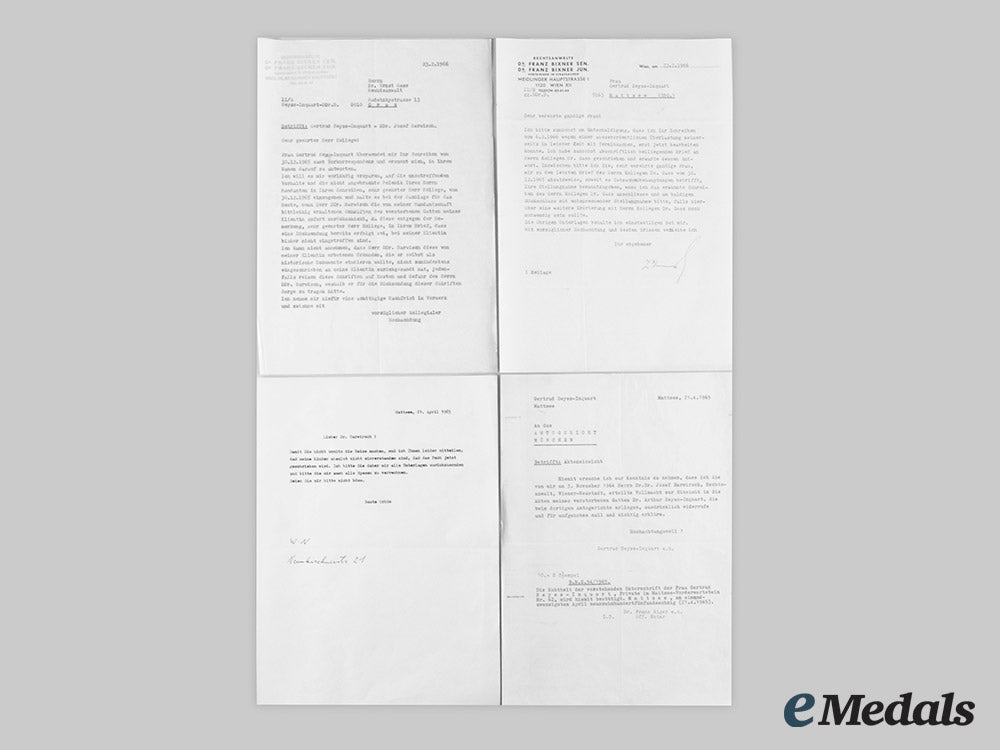

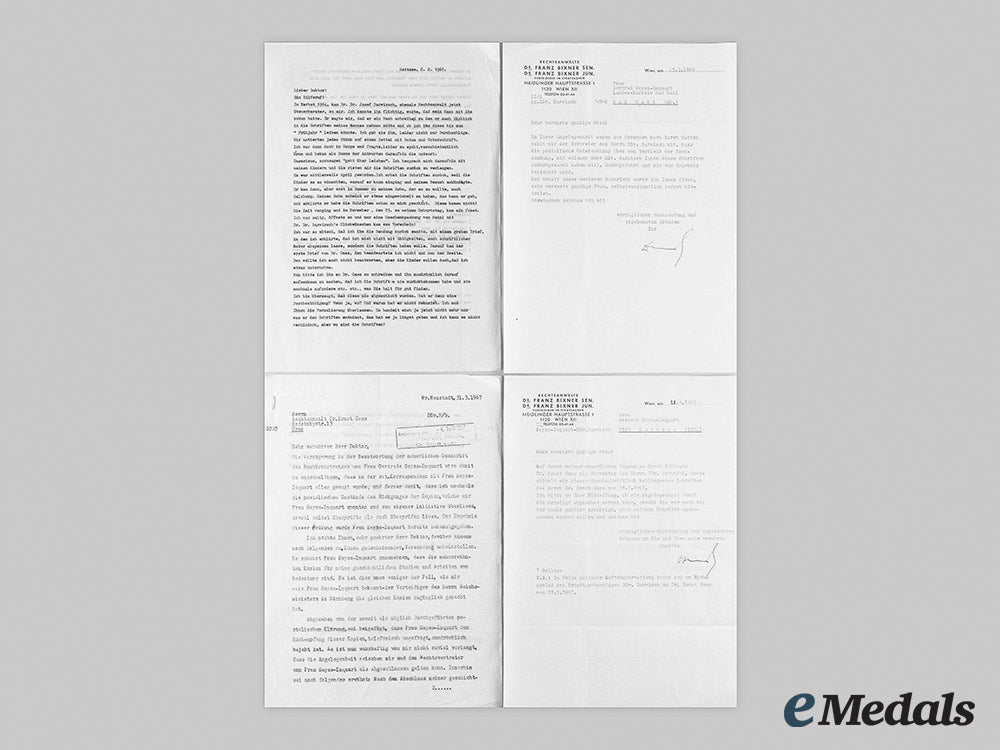

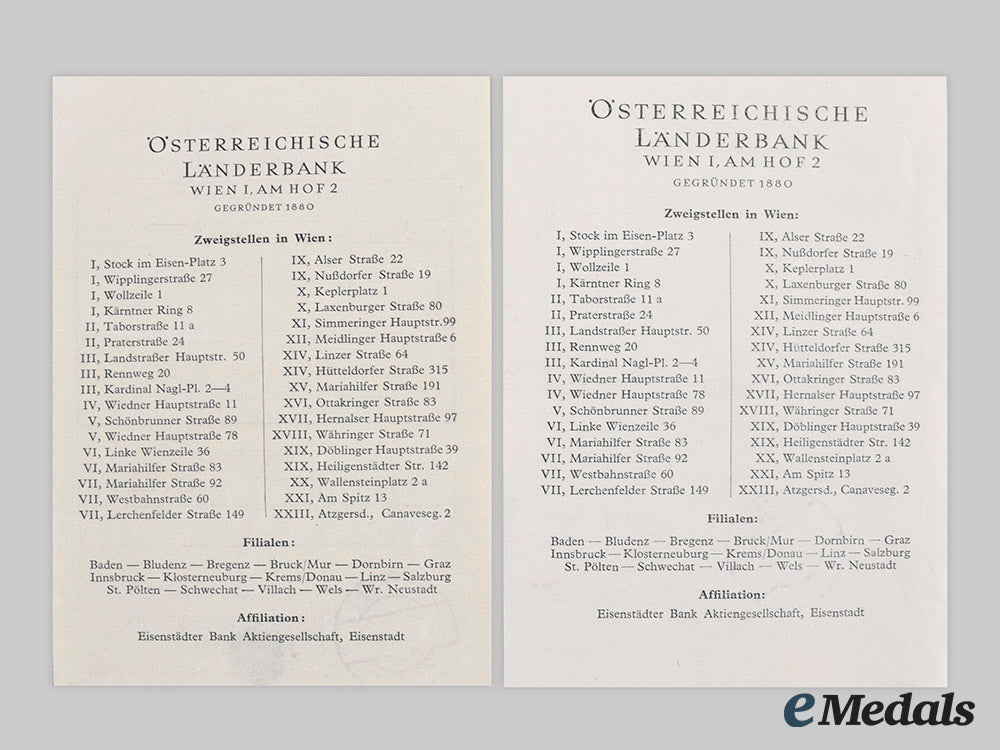

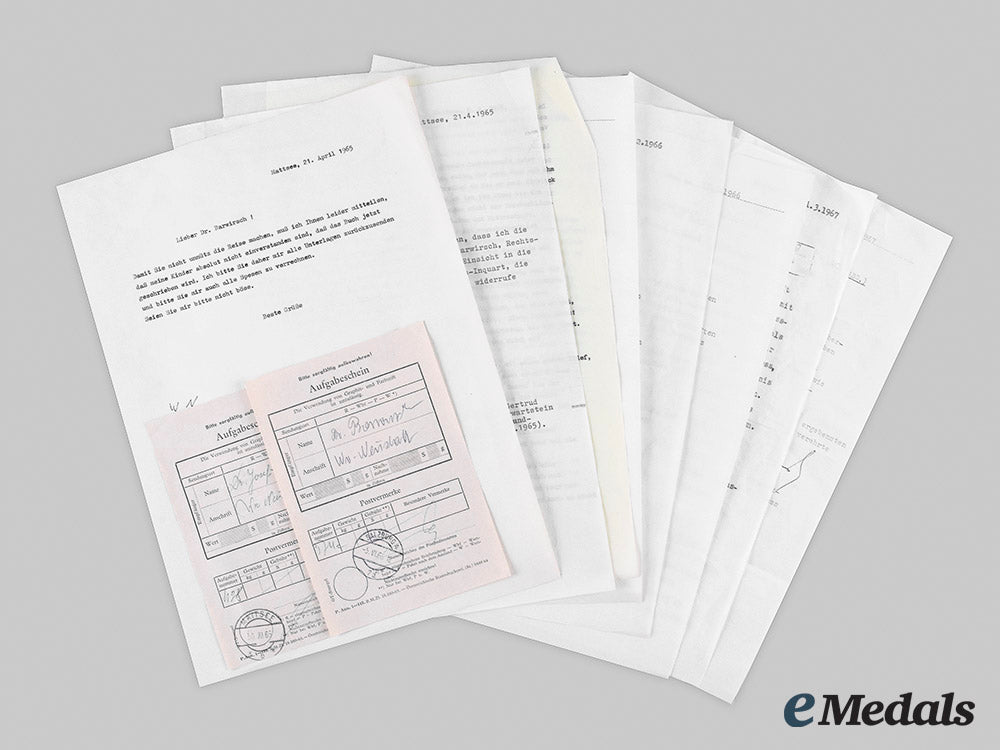

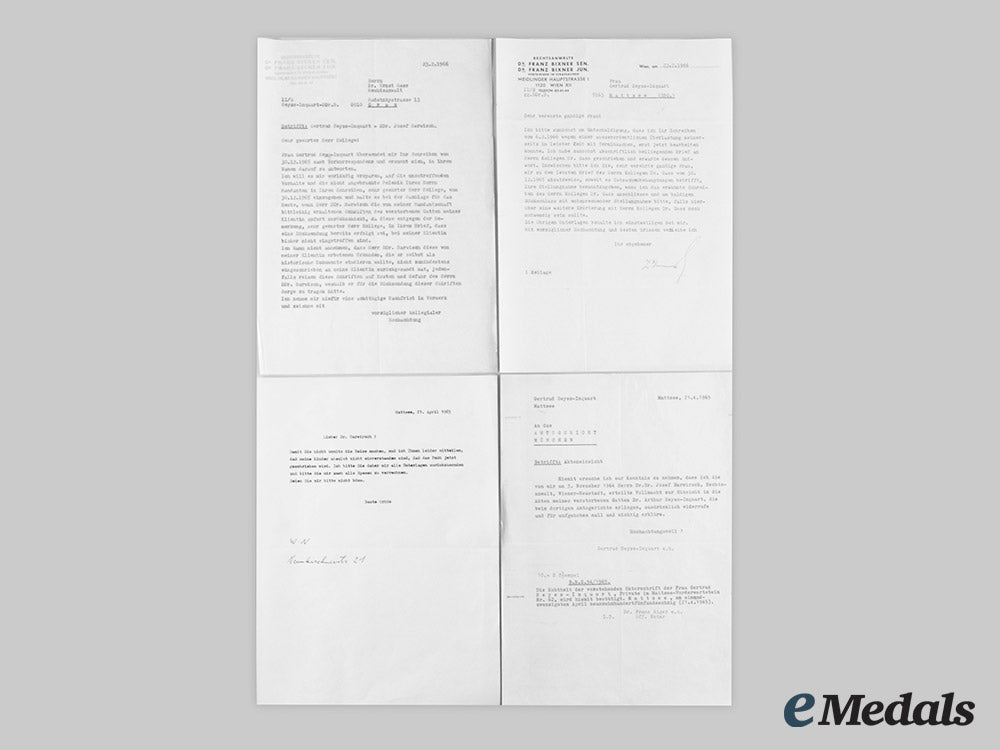

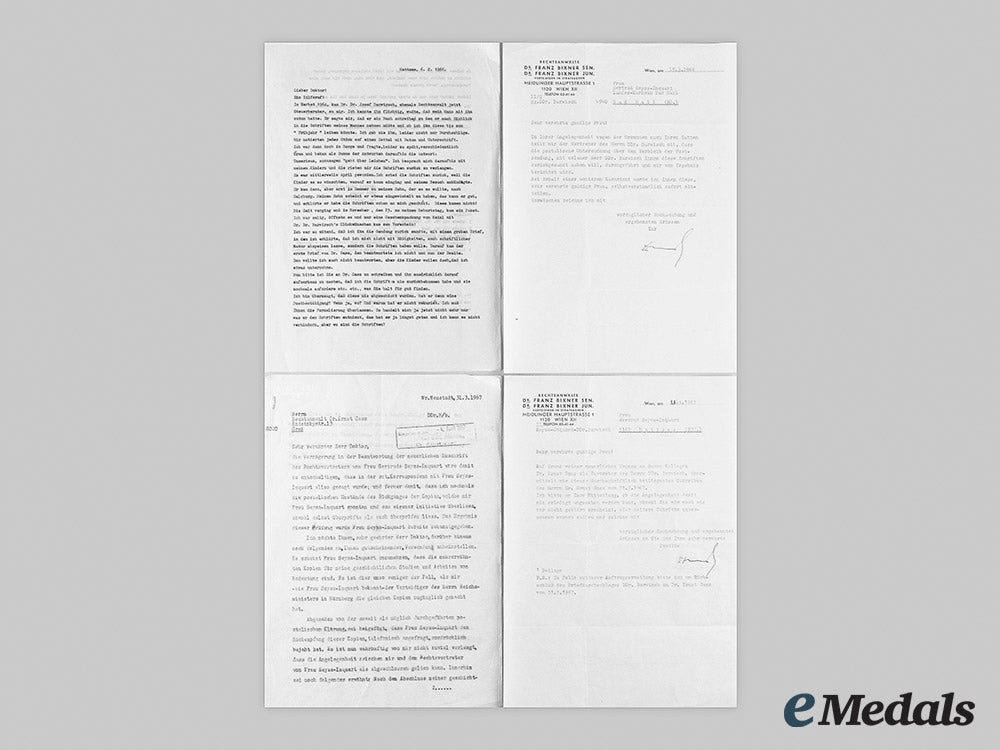

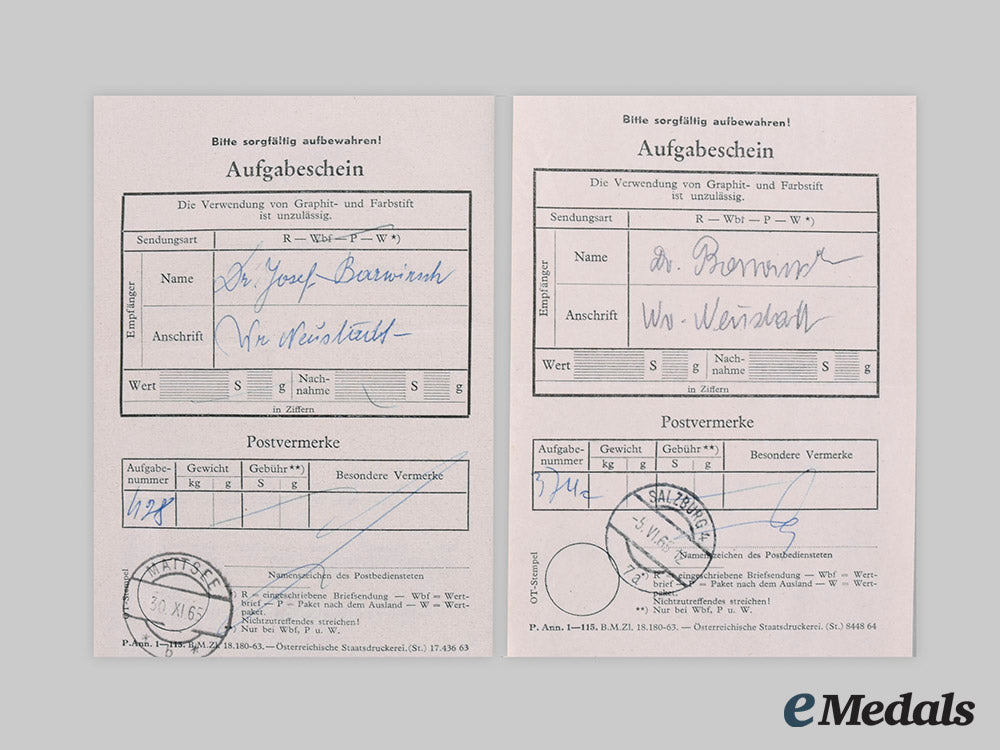

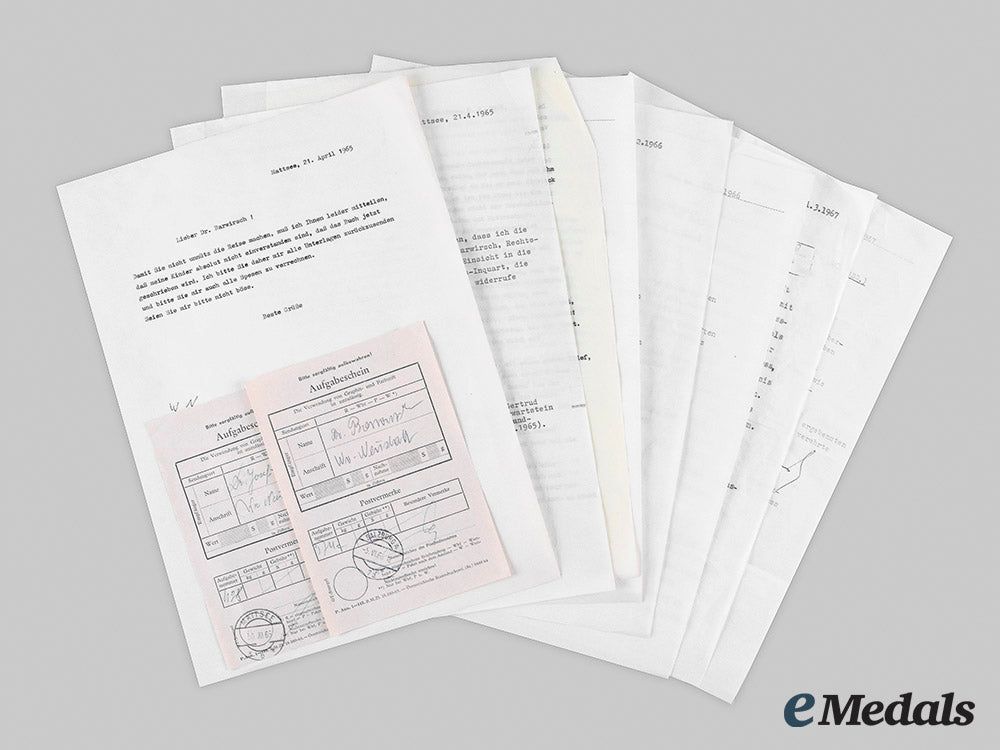

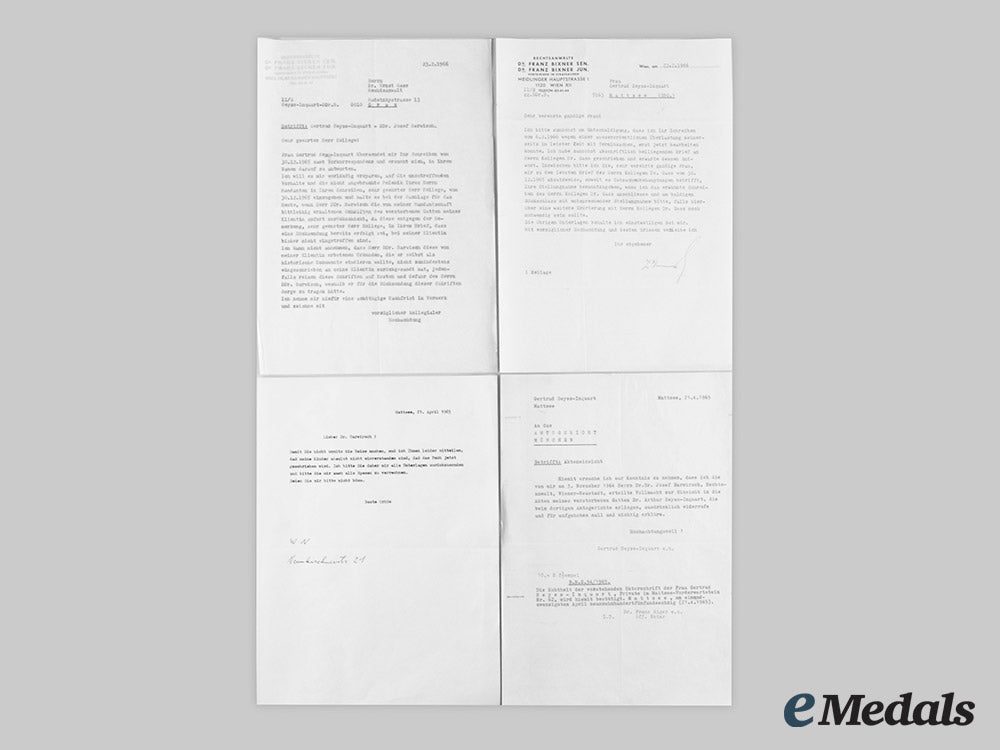

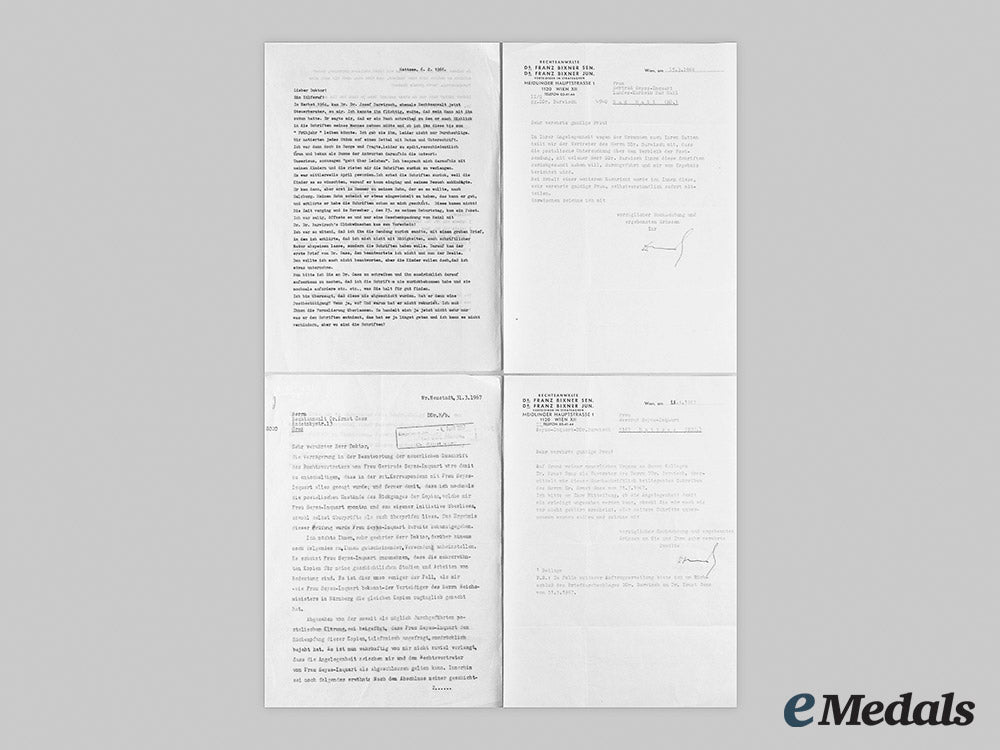

The collection of letters documents an exchange between the widow of Arthur Seyß-Inquart, Gertrude, and a former lawyer and now tax accountant Dr. Barwirsch, using their respective lawyers as intermediaries, Dr. Bixner in the case of Gertrude, and Dr. Gass in the case of Barwirsch.Getrude tells the following story: in the fall of 1964, Barwirsch approached Gertrude to ask for documents and papers of her late husband that he wanted to use for a book he was writing. He asked to borrow the papers until spring of the following year. Gertrude had met Barwirsch before, and she knew her husband had worked with him in the past. She gave him the papers.

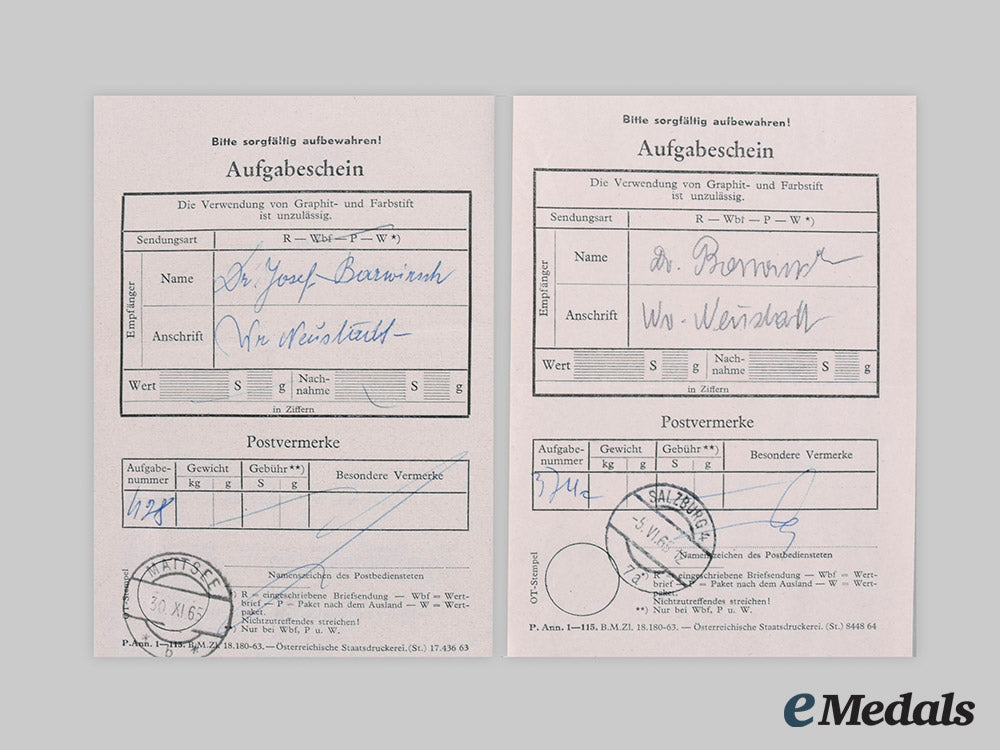

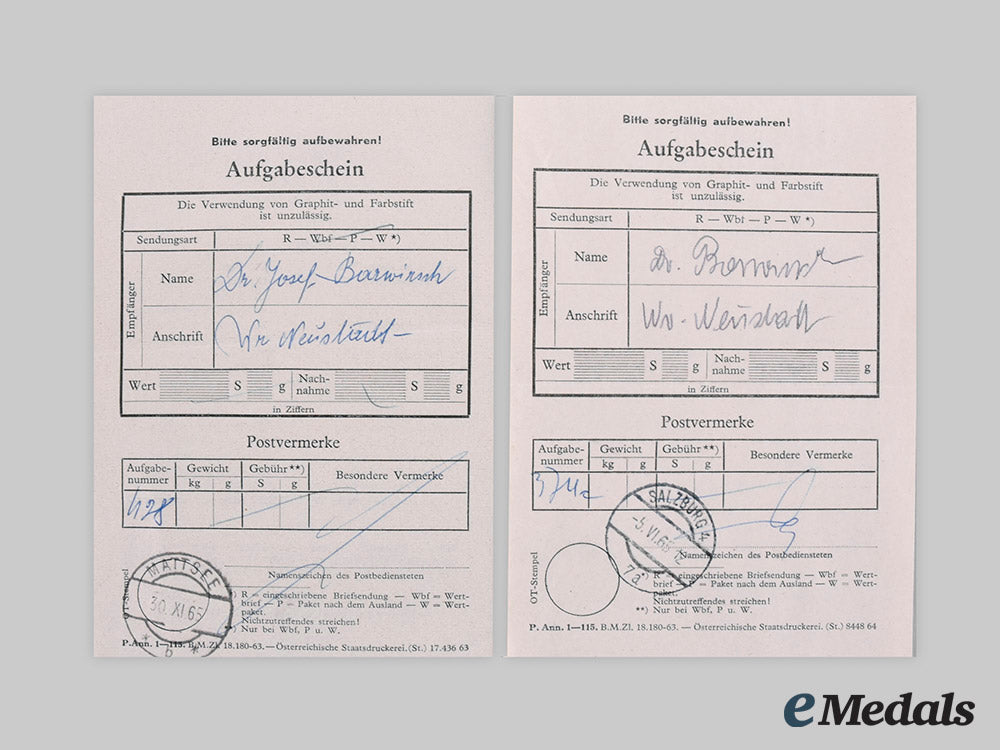

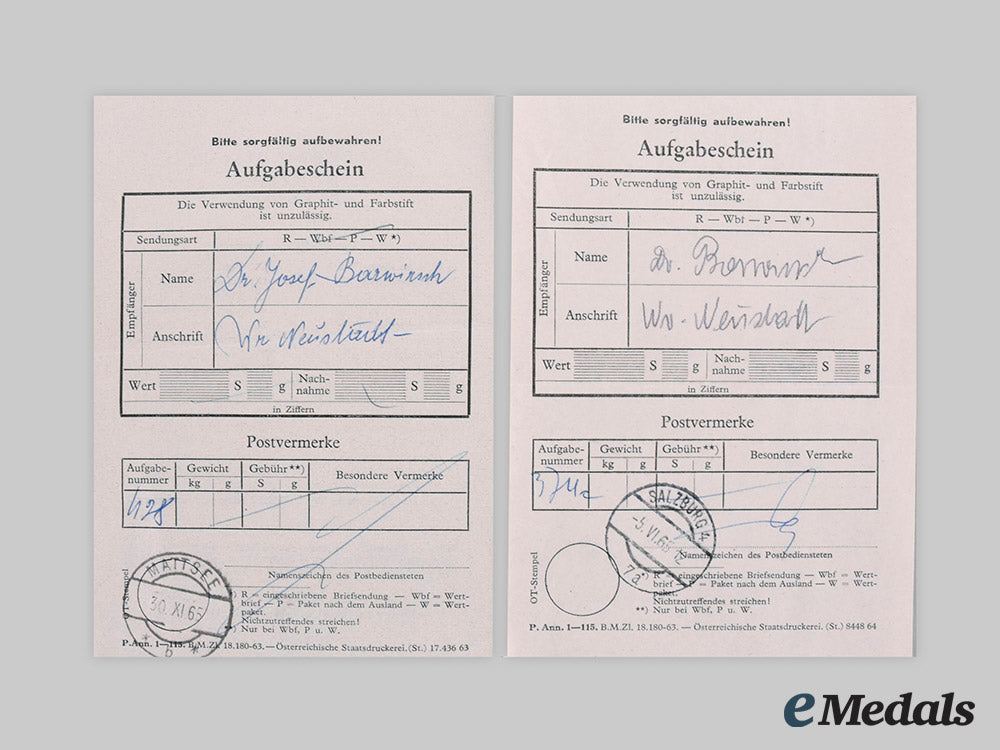

Afterwards, Gertrude began asking around to get some more information on Barwirsch, and she heard that he was dubious and unscrupulous. After talking to her children about the issue, they told her to ask for the papers back. At this time it was April of 1965. Gertrude sent a letter to Barwirsch, asking him to not use the papers for his book after all, since her children didn’t want him to. She also sent a letter to the Munich district court, telling them that she revokes the right she had granted Barwirsch to access the documents of her late husband held by the district court. In the summer, Barwirsch visited Gertrude’s son Richard and told him he had already sent back the papers. However, by November they still had not arrived, so Gertrude wrote an angry letter to Barwirsch. He had his lawyer, Dr. Gass answer the letter, so Gertrude wrote to her lawyer, Dr. Bixner, in February of 1966 to ask him to retrieve the papers for her. Dr. Bixner sent a letter to Dr. Gass, telling him his client, Barwirsch, was responsible for making sure the papers reached Gertrude, and he should try and track them. The next letter in the matter is dated to March 31, 1967. It is a transcript of a letter from Barwirsch to Dr. Gass, which was subsequently sent to Dr. Brixen. In it, Barwirsch states that he had had the postal service track the package, and that Gertrude was told the result of that (not mentioned in the letters), and that she had confirmed on the phone to him that the papers had arrived. With this, Barwirsch sees the case as closed. The final letter is sent by Brixen to Gertrude, sending her the transcript of Barwirsch’s latest letter, asking her if she still wants to pursue the matter.

The letters measure 210 mm (w) x 295 mm (h), presenting various stages of folding and creasing, overall remaining very fine.

Footnote 1: Franz Josef Barwirsch was born on February 16, 1900 in Kirchberg am Wechsel (eastern Austria). He moved to Davos in Switzerland in 1924 to recover from tuberculosis and settled there in 1929, working as a lawyer out of his own practice. In 1931, he became a Swiss citizen.

Davos was a Swiss centre for national socialist ideologists since the early 1930s. Barwirsch developed close ties to most of them, including Wilhelm Gustloff, leader of the swiss branch of the NSDAP.

He also got in contact with the leading national socialists in Austria, including Arthur Seyß-Inquart in early 1939. Barwirsch began writing to Seyß-Inquart, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, and others about his goal of a German Anschluss of Switzerland, similar to that of Austria. Had the Swiss authorities been informed about this, Barwirsch would have been tried for high treason and would have probably received the death penalty.

After the war in late 1945, the Swiss Anschluss letters written by Barwirsch were found among the confiscated documents of Seyß-Inquart. Barwirsch was taken into custody, tried in late 1946, and sentenced to 20 years in prison for high treason. Fortunately for him, the Swiss government had abolished the death penalty for high treason after the war.

In 1954, Barwirsch had been transferred from prison to a sanatorium due to tuberculosis. During his stay, he was sent to a nearby village for a dentist appointment on his own. Instead, Barwirsch fled to Austria.

In 1968, he tried to sue the Swiss government for conducting a “conspiracy” against him, but since the evidence that had led to his conviction was solid, the lawsuit was dismissed. Barwirsch died on June 27, 1985.

Footnote 2:

Arthur Seyß-Inquart was born on July 22, 1892 in the village of Stannern (present-day Stonařov, southern Czech Republic) near the town of Iglau (Jihlava). This was a German speaking community within a Czech dominated area in Moravia, at the time part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. The family moved to Vienna in 1907.

Seyß-Inquart began to study law at the university of Vienna, and earned his degree during the First War in 1917 while recovering from being wounded. As a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian army he saw action in Russia, Romania, and Italy. He received several bravery decorations and at the end of the war held the rank of Oberleutnant (first lieutenant).

After the war, Seyß-Inquart developed close ties with several right wing and fascist organisations, among them the Vaterländische Front (Fatherland Front). He became a successful lawyer and had his own practice since 1921. In 1933, Seyß-Inquart went into Austrian politics and joined the cabinet of chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß.

Through growing influence and support by non other than A.H. himself, Seyß-Inquart eventually became Austrian Minister of the Interior in February of 1938. With the looming annexation of Austria by Germany in March of the same year, Austrian chancellor Schuschnigg stepped down. Seyß-Inquart was chosen as his successor due to immense pressure applied on the Austrian government by the NSDAP.

He served in this position for less than two days, until the Anschluss was completed. Seyß-Inquart signed the documents that legalised the annexation of Austria by Germany. After his office had ceased to exist, he was named Reichsstatthalter (Reich Governor) of the Ostmark, the newly created province that Austria had become as part of Greater Germany.

Being a fanatical anti-Semite, Seyß-Inquart almost immediately ordered the confiscation of Jewish property and had the Austrian Jews sent to concentration camps. He received the honorary SS rank of Gruppenführer in May of 1939, and would go on to become an SS-Obergruppenführer in 1941.

After the attack on Poland at the beginning of the Second War, Seyß-Inquart was named deputy to Hans Frank, the General Governor of occupied Poland. He supported Frank in the deportation of Polish Jews. Seyß-Inquart was also aware of the systematic murder of Polish intellectuals by the German secret service “Abwehr”.

In May of 1940, A.H. named Seyß-Inquart Reich Commissioner of the Netherlands. His policies concerning the Dutch Jews were no different than his policies had been concerning the Jews in Austria and Poland, in that they were ousted from governmental, and leading press and industry positions, their property seized, before being sent to concentration camps. Of the 140,000 Jews that were registered in the Netherlands in 1941, only 30,000 survived the war.

During his reign of terror, Seyß-Inquart also authorized the execution of at least 800 people, ranging from political prisoners to resistance fighters. At the end of the war, he was arrested by Allied forces and became one of the 24 defendants during the Nuremberg trials against the major war criminals. Seyß-Inquart was found guilty in three out of four charges and executed by hanging on October 16, 1946.

Description

The collection of letters documents an exchange between the widow of Arthur Seyß-Inquart, Gertrude, and a former lawyer and now tax accountant Dr. Barwirsch, using their respective lawyers as intermediaries, Dr. Bixner in the case of Gertrude, and Dr. Gass in the case of Barwirsch.Getrude tells the following story: in the fall of 1964, Barwirsch approached Gertrude to ask for documents and papers of her late husband that he wanted to use for a book he was writing. He asked to borrow the papers until spring of the following year. Gertrude had met Barwirsch before, and she knew her husband had worked with him in the past. She gave him the papers.

Afterwards, Gertrude began asking around to get some more information on Barwirsch, and she heard that he was dubious and unscrupulous. After talking to her children about the issue, they told her to ask for the papers back. At this time it was April of 1965. Gertrude sent a letter to Barwirsch, asking him to not use the papers for his book after all, since her children didn’t want him to. She also sent a letter to the Munich district court, telling them that she revokes the right she had granted Barwirsch to access the documents of her late husband held by the district court. In the summer, Barwirsch visited Gertrude’s son Richard and told him he had already sent back the papers. However, by November they still had not arrived, so Gertrude wrote an angry letter to Barwirsch. He had his lawyer, Dr. Gass answer the letter, so Gertrude wrote to her lawyer, Dr. Bixner, in February of 1966 to ask him to retrieve the papers for her. Dr. Bixner sent a letter to Dr. Gass, telling him his client, Barwirsch, was responsible for making sure the papers reached Gertrude, and he should try and track them. The next letter in the matter is dated to March 31, 1967. It is a transcript of a letter from Barwirsch to Dr. Gass, which was subsequently sent to Dr. Brixen. In it, Barwirsch states that he had had the postal service track the package, and that Gertrude was told the result of that (not mentioned in the letters), and that she had confirmed on the phone to him that the papers had arrived. With this, Barwirsch sees the case as closed. The final letter is sent by Brixen to Gertrude, sending her the transcript of Barwirsch’s latest letter, asking her if she still wants to pursue the matter.

The letters measure 210 mm (w) x 295 mm (h), presenting various stages of folding and creasing, overall remaining very fine.

Footnote 1: Franz Josef Barwirsch was born on February 16, 1900 in Kirchberg am Wechsel (eastern Austria). He moved to Davos in Switzerland in 1924 to recover from tuberculosis and settled there in 1929, working as a lawyer out of his own practice. In 1931, he became a Swiss citizen.

Davos was a Swiss centre for national socialist ideologists since the early 1930s. Barwirsch developed close ties to most of them, including Wilhelm Gustloff, leader of the swiss branch of the NSDAP.

He also got in contact with the leading national socialists in Austria, including Arthur Seyß-Inquart in early 1939. Barwirsch began writing to Seyß-Inquart, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, and others about his goal of a German Anschluss of Switzerland, similar to that of Austria. Had the Swiss authorities been informed about this, Barwirsch would have been tried for high treason and would have probably received the death penalty.

After the war in late 1945, the Swiss Anschluss letters written by Barwirsch were found among the confiscated documents of Seyß-Inquart. Barwirsch was taken into custody, tried in late 1946, and sentenced to 20 years in prison for high treason. Fortunately for him, the Swiss government had abolished the death penalty for high treason after the war.

In 1954, Barwirsch had been transferred from prison to a sanatorium due to tuberculosis. During his stay, he was sent to a nearby village for a dentist appointment on his own. Instead, Barwirsch fled to Austria.

In 1968, he tried to sue the Swiss government for conducting a “conspiracy” against him, but since the evidence that had led to his conviction was solid, the lawsuit was dismissed. Barwirsch died on June 27, 1985.

Footnote 2:

Arthur Seyß-Inquart was born on July 22, 1892 in the village of Stannern (present-day Stonařov, southern Czech Republic) near the town of Iglau (Jihlava). This was a German speaking community within a Czech dominated area in Moravia, at the time part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. The family moved to Vienna in 1907.

Seyß-Inquart began to study law at the university of Vienna, and earned his degree during the First War in 1917 while recovering from being wounded. As a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian army he saw action in Russia, Romania, and Italy. He received several bravery decorations and at the end of the war held the rank of Oberleutnant (first lieutenant).

After the war, Seyß-Inquart developed close ties with several right wing and fascist organisations, among them the Vaterländische Front (Fatherland Front). He became a successful lawyer and had his own practice since 1921. In 1933, Seyß-Inquart went into Austrian politics and joined the cabinet of chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß.

Through growing influence and support by non other than A.H. himself, Seyß-Inquart eventually became Austrian Minister of the Interior in February of 1938. With the looming annexation of Austria by Germany in March of the same year, Austrian chancellor Schuschnigg stepped down. Seyß-Inquart was chosen as his successor due to immense pressure applied on the Austrian government by the NSDAP.

He served in this position for less than two days, until the Anschluss was completed. Seyß-Inquart signed the documents that legalised the annexation of Austria by Germany. After his office had ceased to exist, he was named Reichsstatthalter (Reich Governor) of the Ostmark, the newly created province that Austria had become as part of Greater Germany.

Being a fanatical anti-Semite, Seyß-Inquart almost immediately ordered the confiscation of Jewish property and had the Austrian Jews sent to concentration camps. He received the honorary SS rank of Gruppenführer in May of 1939, and would go on to become an SS-Obergruppenführer in 1941.

After the attack on Poland at the beginning of the Second War, Seyß-Inquart was named deputy to Hans Frank, the General Governor of occupied Poland. He supported Frank in the deportation of Polish Jews. Seyß-Inquart was also aware of the systematic murder of Polish intellectuals by the German secret service “Abwehr”.

In May of 1940, A.H. named Seyß-Inquart Reich Commissioner of the Netherlands. His policies concerning the Dutch Jews were no different than his policies had been concerning the Jews in Austria and Poland, in that they were ousted from governmental, and leading press and industry positions, their property seized, before being sent to concentration camps. Of the 140,000 Jews that were registered in the Netherlands in 1941, only 30,000 survived the war.

During his reign of terror, Seyß-Inquart also authorized the execution of at least 800 people, ranging from political prisoners to resistance fighters. At the end of the war, he was arrested by Allied forces and became one of the 24 defendants during the Nuremberg trials against the major war criminals. Seyß-Inquart was found guilty in three out of four charges and executed by hanging on October 16, 1946.

You May Also Like

Germany, Third Reich. A Mixed Lot of Tyrolean Marksmanship Badges

G52930

Germany, SS. An Estonian Waffen-SS Volunteer’s Sleeve Shield

G50381

Germany, SS. A Waffen-SS Sturmmann Sleeve Insignia

G52846

Germany, Third Reich; Slovakia, First Republic. A Mixed Lot of Wartime Postcards

G52905

Germany, Third Reich. A Pair of Tyrolean Marksmanship Badges

G52981

-

Germany, Third Reich. A Mixed Lot of Tyrolean Marksmanship Badges

G52930

Add to CartRegular price $135 USDRegular price $0 USD Sale price $135 USDUnit price / per -

Germany, SS. An Estonian Waffen-SS Volunteer’s Sleeve Shield

G50381

Add to CartRegular price $150 USDRegular price $0 USD Sale price $150 USDUnit price / per -

Germany, SS. A Waffen-SS Sturmmann Sleeve Insignia

G52846

Add to CartRegular price $135 USDRegular price $0 USD Sale price $135 USDUnit price / per -

Germany, Third Reich; Slovakia, First Republic. A Mixed Lot of Wartime Postcards

G52905

Add to CartRegular price $135 USDRegular price $0 USD Sale price $135 USDUnit price / per -

Germany, Third Reich. A Pair of Tyrolean Marksmanship Badges

G52981

Add to CartRegular price $135 USDRegular price $0 USD Sale price $135 USDUnit price / per

Do you have a similar item you are interested in selling?

Please complete the form and our client care representatives will contact you.

Sell Item